KABUL, Afghanistan — Five years after the signing of the Doha Agreement, a question looms: Do the United States and the Taliban still consider it a binding accord, or has it effectively been rendered obsolete?

For the first time, the Taliban publicly declared last Friday that the agreement—which paved the way for the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and is widely viewed by critics as a concession to the Taliban—is now a closed chapter.

In Washington, the agreement remains a subject of debate. Former President Donald J. Trump, under whose administration the deal was signed on Feb. 29, 2020, had previously dismissed it as void during an election debate. While the withdrawal itself took place under President Biden in August 2021, Trump, speaking in a September 2024 debate, criticized the process and declared the agreement “terminated.”

“The agreement said you have to do this, this, this, and they didn’t do it,” Trump said at the time. “The agreement was terminated by us because they didn’t do what they were supposed to do.”

The Taliban’s assessment appears to align with that sentiment. Marking the fifth anniversary of the accord, the group’s chief spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, stated that the deal had outlived its purpose.

“The agreement was valid only up to a certain phase,” Mujahid said. “After that, the Emirate [Taliban] has its own sovereignty. We are not moving forward based on the agreement; we are proceeding according to the principles of our own system. It was an agreement with the Americans that ended at its designated time.”

One of the agreement’s central provisions—the launch of intra-Afghan negotiations to form a new government and end the war—was never fully realized. While the accord facilitated the U.S. military withdrawal, it did not lead to the power-sharing arrangement that American and Afghan officials had once envisioned.

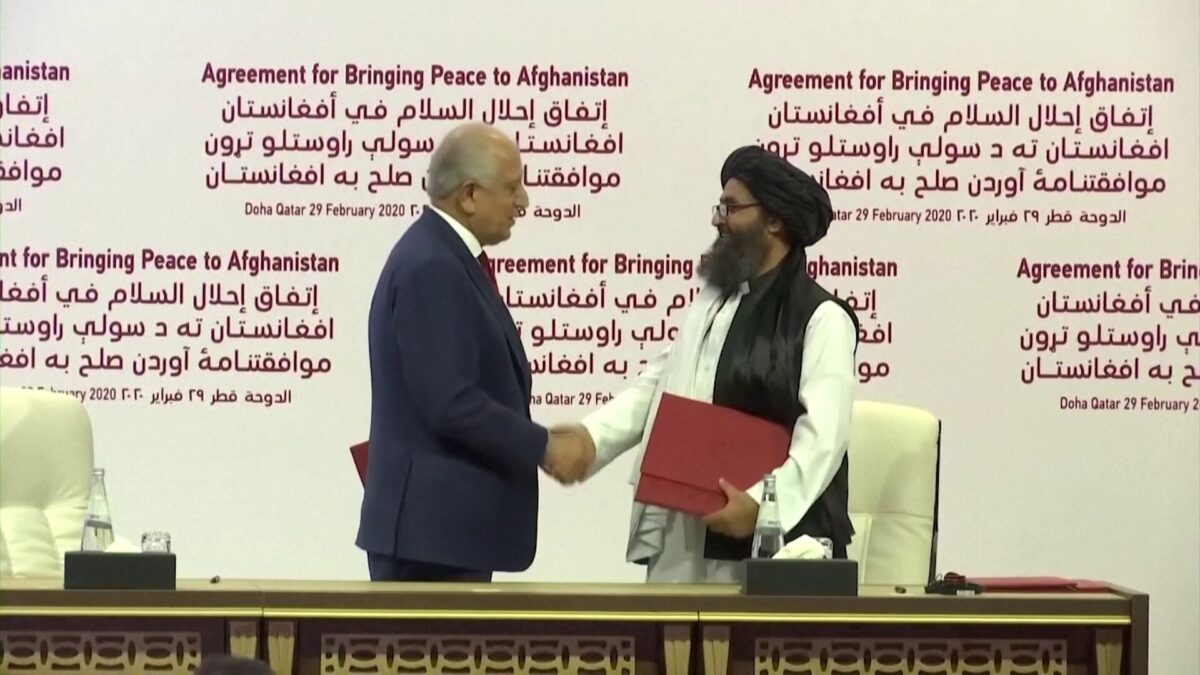

Zalmay Khalilzad, the former U.S. special envoy for Afghanistan reconciliation who led the negotiations and signed the deal alongside Taliban leader Abdul Ghani Baradar, has argued that all parties should return to the agreement to find a way forward for Afghanistan. However, many international relations experts say the document is no longer a viable framework for resolving the country’s ongoing crisis.

“Neither the Taliban implemented the Doha Agreement, nor did the Americans insist on its enforcement,” said Mohammad Nazif Shahrani, a researcher and professor at Indiana University. “As far as I understand, this agreement is no longer valuable—unless both sides retract their previous statements and agree that Afghanistan’s situation can still be assessed and resolved based on the Doha Agreement. However, at this point, I do not see any indication that this agreement will be revisited.”

Beyond its publicly disclosed provisions, the Doha Agreement is also believed to contain classified elements. Some Afghan citizens have previously told Amu TV that they view the agreement as a betrayal, with many believing it amounted to “the surrender of Afghanistan to the Taliban.”

The Biden administration has largely shifted its focus away from Afghanistan, and the Trump administration—if returned to office—has yet to outline a specific policy on the country. However, Trump has repeatedly emphasized the need to reclaim U.S. military equipment left behind, much of which fell into Taliban hands following the American withdrawal.

As the agreement’s legacy continues to be debated, the fate of Afghanistan remains uncertain—shaped more by Taliban rule than by any commitments once outlined in the deal.