Some female students attending Taliban-run religious schools have shared with Amu that their education is focused not only on traditional Islamic studies but also on how to raise “mujahid” (holy warrior) children and serve their husbands. These students report that they are being directed to avoid modern subjects, and much of their curriculum encourages extremist ideologies.

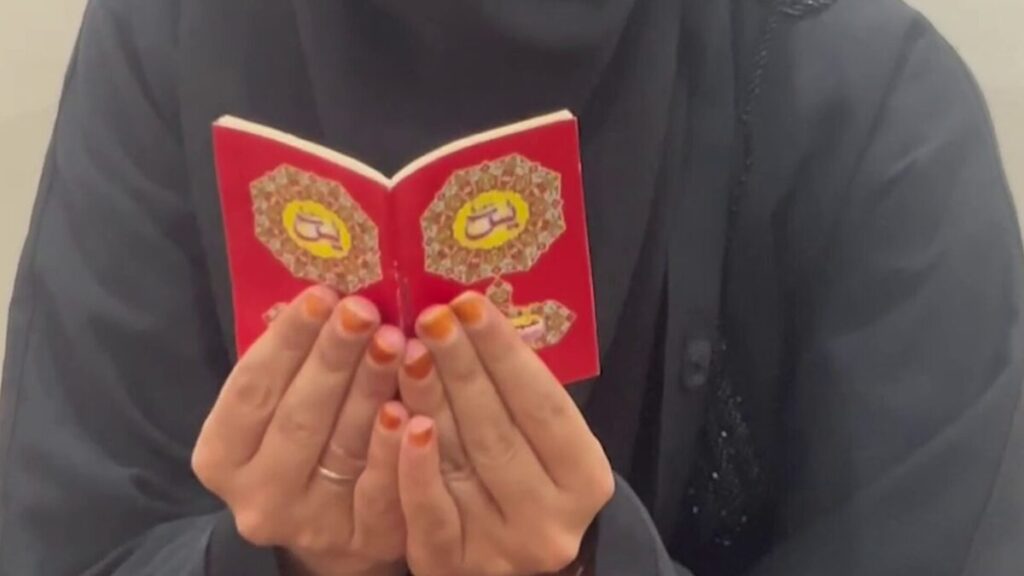

Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 and their subsequent ban on formal education for most girls, thousands of Afghan girls have turned to religious schools, or madrasas, as their only option for education.

A curriculum rooted in tradition and extremism

The curriculum in Taliban-run madrasas for girls is structured around three levels, primarily focusing on Islamic jurisprudence and religious texts. Girls study subjects such as Sarf Baha’i (Arabic grammar), Shurut al-Salah (the conditions of prayer), Zad al-Talibin (a religious text), Dars al-Balagha (rhetoric), and Usul al-Fiqh (principles of jurisprudence).

In addition to these formal lessons, students receive informal instruction on the role of women in society, which emphasizes domestic duties, obedience to husbands, and raising children for jihad.

Fatima, a former eighth-grade student who once dreamed of becoming a doctor, was forced to abandon her plans after the Taliban shut down schools for girls.

She enrolled in a religious school in Herat, hoping to continue her education in some form. However, what she encountered was vastly different from her previous schooling.

“In this madrasa, they teach us about fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence], how women should behave in society, and how to raise ‘mujahid’ children,” Fatima explains. “My perspective has changed. Now, I’m only interested in studying religious subjects.”

Fatima says she is now learning that women should not be visible in public, as this is considered sinful. She and her classmates are repeatedly told that a woman’s primary role is within the home, and that their education is solely for the purpose of becoming better wives and mothers.

“They teach us that the only place a girl should study is at the madrasa, and they constantly emphasize how important it is to raise pious and righteous children who will one day fight for Islam,” Fatima adds.

Lessons in obedience and domesticity

Other students have had similar experiences. Safia, another student, says that the madrasa instructors place a strong emphasis on the importance of marrying a devout Muslim man and devoting oneself to household duties.

“We learn a lot about fiqh and Quranic interpretation, but what they stress the most is that Muslim women must avoid sin. One way to do that is to marry a pious man, stay at home, and dedicate yourself to housework, so you can raise good, righteous children,” Safia says.

The teachings in these madrasas align with the Taliban’s interpretation of Sharia law, which restricts women’s rights and freedoms, particularly in education and public life. For many girls, the madrasas are their only option, as the Taliban have banned girls from attending secondary schools and universities.

Extremist ideologies take root

Some girls report that the madrasas are not only focused on traditional Islamic education but are also instilling extremist beliefs.

Mina, a student in another religious school, says that the lessons are heavily religious, with no attention paid to modern sciences or secular subjects. “We’re taught only religious topics, like the role of women in Islam. But I think it’s important for us to learn modern sciences too. I hope that schools reopen so we can study both,” she says.

According to Mina, the madrasas’ focus on religion is paired with a broader goal of promoting a conservative, rigid worldview that discourages critical thinking and open inquiry. Students like her feel that they are being groomed to become obedient wives and mothers, with no exposure to the subjects that might offer them a broader understanding of the world.

The role of modern education in Islam

Despite the Taliban’s restrictions, some Islamic scholars have emphasized that Islam encourages both men and women to pursue education, including modern subjects.

Abdul Saboor Abbasi, a religious scholar, notes that Islam places no restrictions on women learning sciences or other modern disciplines.

“Islam never differentiates between men and women when it comes to acquiring knowledge. Learning is considered obligatory for both men and women,” Abbasi says.

This view contrasts sharply with the Taliban’s actions, which have resulted in the closure of thousands of schools for girls across Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s Ministry of Education now oversees more than 21,000 religious schools, with around three million students enrolled. In contrast, under the previous Afghan government, there were only about 1,800 madrasas in the country.

A rise in madrasas and competition among Taliban officials

Observers note that the proliferation of madrasas since the Taliban’s return to power is not only about providing religious education.

Some suggest that there is competition among Taliban officials to establish more schools, as this helps them gain influence and loyalty from local communities. There are concerns that this could lead to the creation of future militias, as each faction within the Taliban may seek to cultivate its own base of fighters through these schools.

“The number of religious schools has skyrocketed since the Taliban came to power,” says one education expert. “It seems like every Taliban commander wants to open his own madrasa to increase his influence and ensure that he has a loyal group of young men to rely on in the future.”

A future shaped by religious education

For many girls attending Taliban-run madrasas, the future is uncertain. With no access to modern education, they are left with few options beyond the narrow roles prescribed for them by the Taliban. While some, like Fatima and Safia, have resigned themselves to this fate, others, like Mina, still hope for a return to formal schooling.

“I want to study science and other subjects, but right now, we don’t have that option,” Mina says. “I just hope the schools reopen someday, so we can learn more than just religion.”

For now, the Taliban’s religious schools continue to shape the minds of a new generation of Afghan girls, emphasizing traditional gender roles, obedience, and a future dedicated to religious devotion and domestic life.

Whether these girls will one day have the opportunity to pursue a broader education remains an open question, as Afghanistan’s educational system remains deeply divided between those who support the Taliban’s strict interpretation of Islam and those who hope for a return to more inclusive schooling.