For centuries, Herat’s calligraphers have etched the words of history onto stone, preserving the cultural identity of Afghanistan. But decades of war have devastated this delicate art, leaving many inscriptions damaged or destroyed.

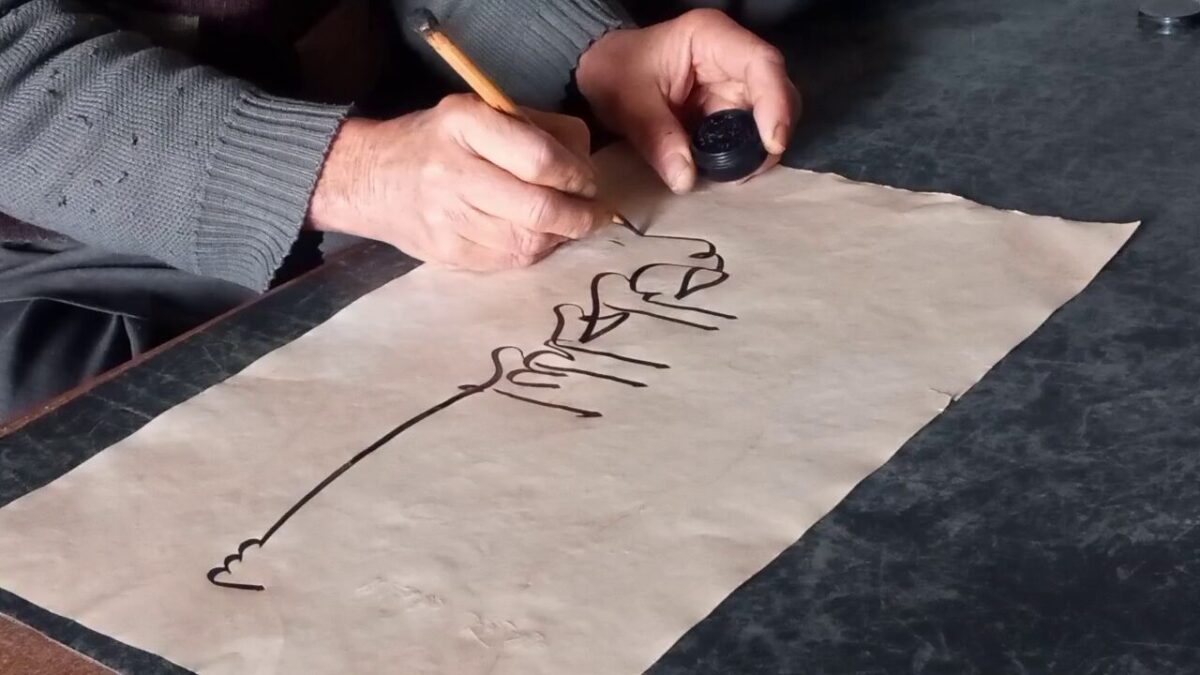

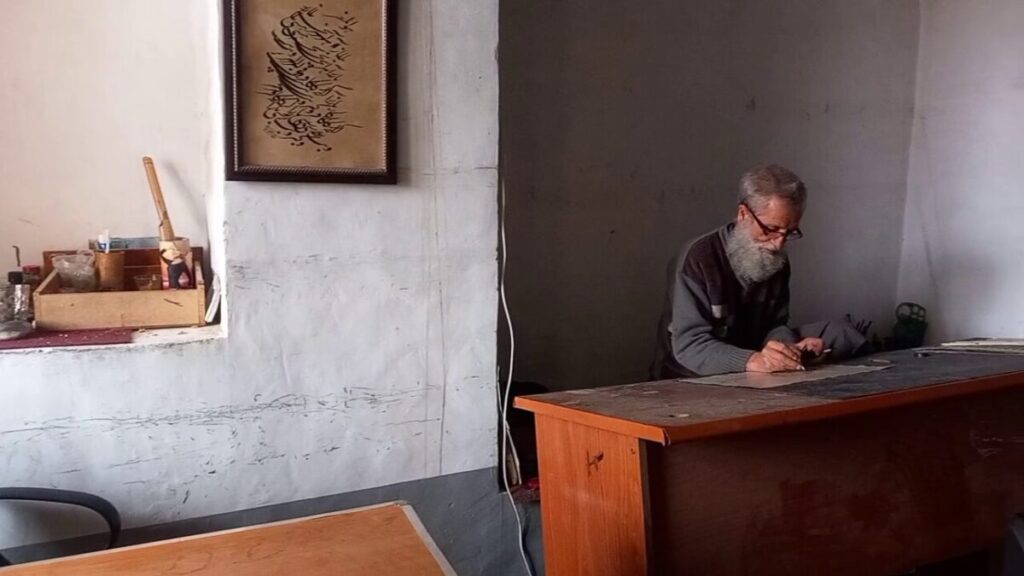

Among those fighting to keep the tradition alive is Ahmad Sabri, a master calligrapher who has handwritten several Qurans. Now an aging artist, he continues to inscribe his generation’s cultural legacy for the next, ensuring the echoes of history are not lost.

A legacy scarred by war

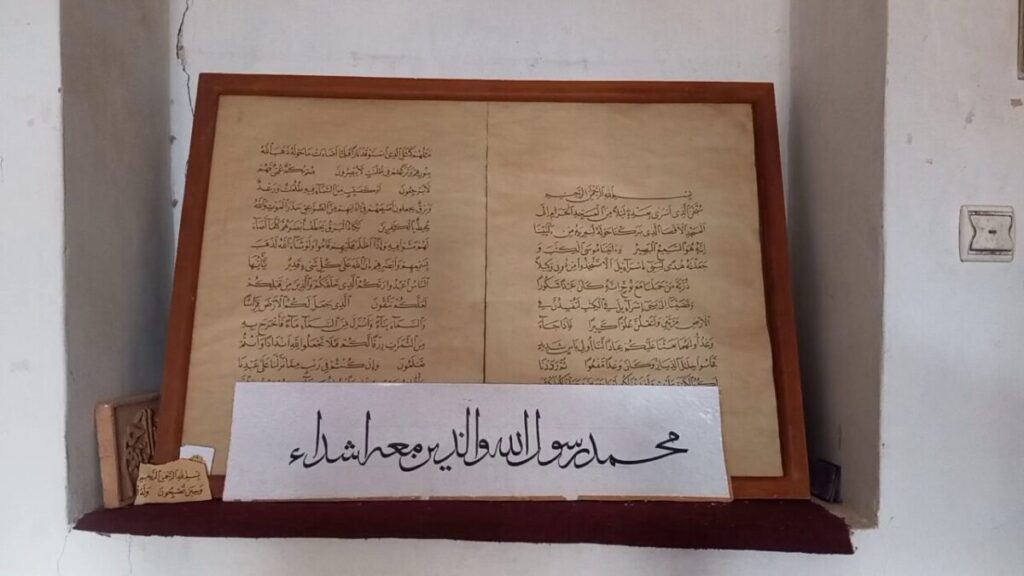

“Many of Herat’s historical calligraphic works have been lost due to war,” Sabri said. “From the time of British occupation to the present, some of our most treasured inscriptions have been erased. Only fragments remain.”

Among the most significant surviving examples of Herat’s calligraphy are the Great Mosque of Herat and the shrine of Khwaja Abdullah Ansari, revered for their intricate inscriptions.

Calligraphers typically work on durable surfaces, hoping their scripts will endure for generations. However, war has been merciless, with bullets and bombs damaging even the most resilient stone inscriptions.

A forgotten art in modern Afghanistan

Once highly regarded, calligraphers now struggle to make a living, facing economic hardship and fading recognition.

“Herat’s historical sites have two designated calligrapher positions,” said Raqibullah Rizwani, the Taliban-appointed head of historical monuments in Herat. “These artists repair inscriptions when they are at risk of collapse.”

The city’s monuments feature various calligraphic styles, from Naskh and Thuluth to Kufic.

“We have many historical sites decorated with Islamic calligraphy, particularly in the Thuluth and Kufic scripts,” said Jalil Ahmad Tawanah, head of Herat’s Calligraphers Association.

Despite the challenges, Herat’s calligraphers continue their work, carving history into stone, determined that no hardship will erase the cultural heritage they have dedicated their lives to preserving.