In recent months, Taliban and the Islamic Republic of Iran have drawn widespread domestic and international criticism for enacting stringent laws rooted in their ideological interpretations of Islam. Taliban’s Law on Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice and Iran’s Hijab and Chastity Law serve as tools for both rules to reinforce their authority while shaping public behavior. These measures have provoked intense reactions, particularly from human rights advocates, who view them as a direct assault on individual freedoms, particularly those of women.

Although Afghanistan and Iran share cultural and historical ties, their rulers’ approaches to governance are shaped by distinct sectarian interpretations of Islam—Sunni Hanafi in Afghanistan and Shia Jafari in Iran. This divergence informs the nuances of their respective legal frameworks.

Legal frameworks

The Taliban’s Law on Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice was enacted on July 31, 2024, and published in the official gazette. The law comprises 37 articles divided into four chapters, addressing issues such as the responsibilities of enforcers, the scope of moral oversight, and punishments for violations. Its stated aim is to regulate personal and social behavior in alignment with the Taliban’s interpretation of Islam.

Similarly, Iran’s Hijab and Chastity Law, passed this year, spans 74 articles across five chapters. It details general principles, the roles of public institutions, individual obligations, and punitive measures for non-compliance. Like Afghanistan’s law, it seeks to enforce Islamic values in public and private life, with a strong focus on controlling women’s attire and conduct.

Shared features

Despite differences in their sectarian foundations, the two laws share significant commonalities:

Ideological Roots: Both laws are deeply rooted in Islamic ideological frameworks, with Afghanistan leaning on Hanafi jurisprudence and Iran on Jafari interpretations. Both seek to create a society that adheres strictly to their vision of Islamic principles.

Religious Justification: Each law justifies its provisions through religious texts, presenting itself as a safeguard of Islamic values.

Focus on Women’s Attire: The central target of both laws is women’s dress, with an emphasis on mandatory veiling as a marker of moral and religious compliance.

Control Over Individual Lives: Both laws extend beyond dress codes, regulating individual behavior and interactions to align with their governments’ moral agendas.

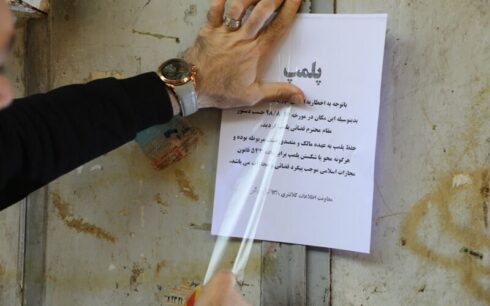

Institutional Enforcement: Afghanistan’s Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice and Iran’s Morality Police are tasked with enforcing these laws. Both institutions have been criticized for their invasive and coercive methods.

Restrictions on Women’s Rights: Both laws severely curtail women’s freedoms, imposing strict limits on their civil, political, and social rights.

Divergences

Despite these similarities, the two legal frameworks differ in several key respects:

Legal Sources: Afghanistan’s law is based on Hanafi jurisprudence, while Iran’s draws from Jafari principles. This divergence reflects the broader sectarian divide between Sunni and Shia Islam.

Severity of Restrictions on Women: In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s law imposes almost total exclusion of women from public life, banning education and employment after puberty. In Iran, women can study and work but must comply with strict dress codes under the Hijab and Chastity Law.

Gender Segregation: Afghanistan enforces absolute gender segregation in most areas of public life, while Iran allows limited interaction under strict guidelines.

Men’s Attire and Behavior: Afghanistan’s law imposes stricter dress and grooming standards on men, whereas Iran’s law primarily focuses on women.

Employment Restrictions: Afghan women are barred entirely from public-sector jobs, while Iranian women are permitted to work if they adhere to dress codes.

Access to Education: Afghan women are largely denied education beyond primary school, while Iranian women can pursue higher education under the constraints of the Hijab and Chastity Law.

Broader social impacts

Both laws have far-reaching implications for individual freedoms and societal dynamics. They restrict fundamental rights such as the freedom to choose one’s attire, pursue education, seek employment, and engage in recreational or social activities.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s law has drawn widespread condemnation from international organizations, which argue that it systematically erases women from public life. Iran’s law, while less draconian, has also sparked significant domestic and international backlash, with critics decrying it as an assault on women’s autonomy and a tool of authoritarian control.

The enforcement of these laws has led to resistance from both civil society and international actors. Human rights organizations, feminist movements, and global leaders have spoken out against these measures, highlighting their impact on women’s rights and broader societal freedoms.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s policies have been denounced as a regression to the group’s harsh rule in the 1990s, prompting calls for international intervention to restore women’s rights. In Iran, the Hijab and Chastity Law has reignited domestic protests, with women’s rights activists and their allies demanding greater freedoms and challenging the regime’s authority.

The Law on Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice in Afghanistan and the Hijab and Chastity Law in Iran are emblematic of the broader struggle between authoritarian interpretations of religion and the universal pursuit of human rights. While both governments justify their actions as necessary to uphold Islamic values, their measures have only deepened societal divisions, restricted freedoms, and attracted global condemnation.

The world watches as these laws unfold, challenging the resilience of the individuals and communities they seek to control and raising urgent questions about the role of religion, gender, and power in shaping the modern state.

Nasrullah Stanikzai is a political analyst and former professor of law and political science at Kabul University.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Amu.