Hundreds of days have passed since those harrowing moments.

Back then, we had grown accustomed to swallowing our tears with each bite of food, silently grateful for the meals we had and the roof over our heads—blessings that many around us lacked. For days, we witnessed chaos and disorder in every step we took: on sidewalks, in front of bakeries, in parks that had, until recently, been bustling with people. There was little we could do, other than tighten our scarves with an extra pin or two, hoping our trembling lips and tear-choked throats would go unnoticed by others.

Despite our internal turmoil, we had to be thankful. We had to find some joy in being in Kabul, the capital where the president, ministers, and lawmakers resided. Kabul wouldn’t fall as easily as the provinces—or so we believed.

That day marked the end of the semester exams. As I left home, I recited Qul Hu Allah with a sincerity I had never known before, spreading my breath over my body as if creating a shield. What else could I do? No one knew what the next moment would bring—only God knew…

It was past ten o’clock. I had just finished grading the ethics exam for my fifth-grade students and hurried them home as quickly as I could. After handing in the day’s results to the school office, I took a moment to look out the window of my second-floor classroom. It faced the main road, now more crowded than I had ever seen.

Cars moved like an army of ants, so tightly packed together that I thought, The cars have taken over the sidewalks…

Further ahead, the number of tents in the park had multiplied since a few days ago. The tents were no longer uniform in color; they had become a patchwork, like the ribbons I had seen tied to the branches of the trees at the Shah-e-Doshamshera Shrine.

Red, pink, blue, and colorless… Most were colorless, like the hours ahead of us, whose hues we could not yet foresee.

At that hour, we all knew how dire the situation was, but we also had to decide: Should we go to university or not?

We didn’t get the chance. The sound of gunfire silenced all the noise around us: one shot, then two, then three… Faces turned pale, and hands began to tremble. Could it be that Kabul had fallen?

But we were wrong. Two or three minutes later, the news came: “The gunfire came from across the street, in front of the bakery.”

Displaced people from the provinces had quarreled over a few loaves of bread, and the argument had escalated into a fistfight and then gunfire. It was hard to believe, but it was true: the people who had fled the war were now fighting among themselves. Why?

Because for two days, no one had brought them bread, water, or any other aid—not even for a photo op on social media.

It was difficult, but I still wanted to believe that the turmoil would pass. It seemed impossible.

A little before noon, with a heart heavy with disbelief, I said goodbye to my colleagues and quickly headed home.

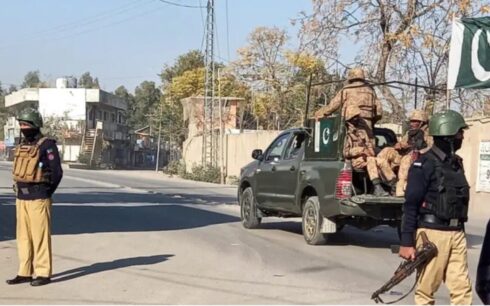

Kabul was engulfed in silence. Though the roads were still congested, everything was so eerily quiet it seemed as if no one alive was in the cars. The congestion, however, was different: a convoy of military tanks was pushing the cars aside with arrogant ease. I was terrified, but I had to make it home. When I arrived, my father was there; he was the one who told me Kabul had fallen. This time, it wasn’t a rumor or a fear—it was the truth. Kabul had fallen.

Just an hour later, I looked out the window: there was no more traffic, not even a mosquito buzzing on the street. The city, as far as the eye could see, had become as silent as a graveyard.

Kabul had fallen, and we, like children who understand the value of their mother only after her death, were left speechless under the weight of the news.

Hundreds of days have passed since then. Afghanistan has been upturned like the land of Lot. We saw—and wished we hadn’t—how people fell from the sky to the earth.

Since those days, we have adapted; we have learned to swallow our tears in silence. Sometimes, those tears fall, especially after hearing news about our situation—our situation, meaning that of me and my fellow women, the men who must pay the price for wearing military uniforms, the old men who have suffered strokes because their sons are missing, the women who beat their chests in mourning for husbands they haven’t seen since they said goodbye in the morning, not knowing whether they are dead or alive…

And then there is the matter of gratitude. We must be grateful and never forget which country we live in and that we have an Islamic government. Of course, in this regard, we are allowed to give thanks out loud.

All these feelings still linger, except when we close our eyes and lose ourselves in dreams of a different destiny… Dreams and visions remain unspoken; these are still ours, hidden. Of course, if they could, they would try to take these away too, but they cannot. They have dimmed them, but they have not extinguished them—not even since those days.

H. Rahnaward is a poet and writer whose stories and poems have been published in national and international outlets.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Amu.